▻ Randall Grahm

In conversation with Randall Grahm

““We have so many more opportunities than the Europeans, and we don’t take advantage of those opportunities, it’s a shame and a missed opportunity””

Episode Summary:-

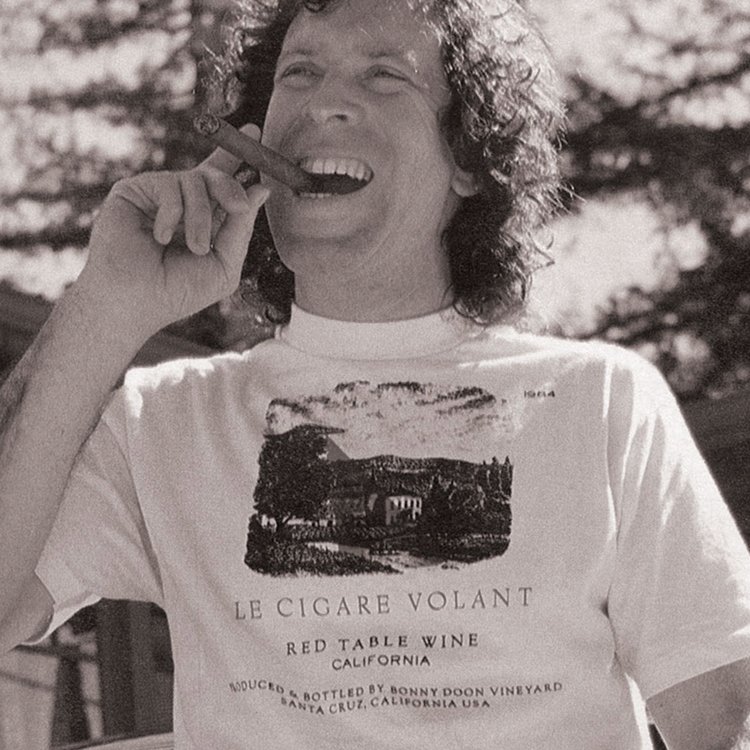

In this episode of Great Wine Lives, Elin McCoy talks with Randall Grahm, the iconoclastic, energetically quirky winemaker who founded Bonny Doon Winery in the mountains of Santa Cruz, in California’s Central Coast region in 1983, and became famous for numerous innovations, especially in specializing in wines made from grape varieties of Southern France, which led to him becoming the figurehead of an offbeat wine movement known as the “Rhône Rangers.” He was an early advocate of organic and biodynamic viticulture in California, as well as micro-oxygenation and other winemaking techniques, screwcaps, and, especially notable, humour in wine labelling and presentation.

Elin asks how Randall got involved with wine, and his answer is simple: After finishing his university studies, he dropped in to a wine shop near his family home in Los Angeles, was offered a charge account, bought some wine, liked it very much, and took a job in the shop, for the “opportunities to taste great wines, pretty much regularly – a happy accident,” he says, adding that he appreciated wine’s aesthetic aspects, and how selling it gave him a further appreciation, of “how important it was to communicate how evocative it was.” He decided on a career-making wine.

He tells Elin how his first mentor was Kermit Lynch, an importer and retailer in Berkeley, California, with a special interest in wines of southern France, especially Provence. Randall’s aspiration was to make great Pinot Noir: “I loved Burgundy,” he says, “but it’s hard to do perfectly.” He had tasted fine Pinot Noir from the Santa Cruz area, and settled there, but the microclimate in his spot was too warm. “I needed a Plan B,” he relates.

Randall tells Elin how he’d been buying Grenache and later Syrah grapes, to make an everyday wine, when Lynch mentioned Mourvedre as a possible addition, and he found some, bought it, added it to the blend, and “it was great, and there was the plan.”

That blend became a wine known as La Cigare Volant (The Flying Cigar, a spoof on a Rhône edict forbidding flying saucers from landing in their vineyards). The label featured a spacecraft over a vineyard, a comic provocation that got attention; Bonny Doon was launched, and landed firmly in the minds and glasses of American wine drinkers.

Elin then asks about the fact that he’s always talked about admiring “wines of place,” and exalting terroir, and wonders whether some of his efforts were more about technique. Grahm admits there may be some truth in that, but declares that his realization of this led him to organic farming, then biodynamic wherever possible: “I love wines from well-cared-for soil, they have a life-force, they’re dynamic.”

Meanwhile, he was having fun, as Elin notes. He created a pair of lower-priced labels, a red blend called Big House, and a Riesling, mostly from Washington State grapes, called Pacific Rim. He also bottled some Italian varieties, with odd names, such as Heart of Darkness, with exotically humorous label illustrations by the equally iconoclastic Ralph Steadman. “One was semi-pornographic,” he tells Elin, “and when the US government agency that oversaw wine rejected it, Ralph wrote a 10-page single-spaced letter of complaint.”

Realizing that he’d gotten somewhat off the track, Randall sold the Big House and Pacific Rim brands, shrinking the winery’s output from 450,000 cases to 40,000. He explains to Elin that this freed him to spend more time making wine than marketing it. “It was like flying an airplane without an engine,” he notes wryly. “Finding the right scale was elusive.”

Elin gets him back on track by mentioning his pioneering—the micro-oxygenation, experiments in making wine from frozen grapes, and especially bottling his premium wines with screwcaps, which advanced the use of those closures, and recalls his notorious “Death of the Cork” dinner, which featured a casket full of corks and a mock-serious eulogy from Jancis Robinson and an announcement that this was the end of 17th Century technology—“the cork.” His sense of humour was very rare, she notes, but he demurs: “Maybe humour is a double-edged sword, maybe some of the wines haven’t been taken as seriously as they should have been.”

Elin then follows up with a question about the Rhone Rangers tag; was it good for him, in the long run? On balance, he says, it was mostly a good thing, but he doesn’t want to be the Rhone Ranger any more: “The term was self-limiting, in the end. The most important thing is being unique, not defined in terms of someone else.”

He sold Bonny Doon at the beginning of 2020, after planting a vineyard further south, and is concentrating, he says, on making wines of a special place, with some old-fashioned techniques, like bush vines rather than canopies, unirrigated, using biochar (carbon-rich biomass residue, a soil amendment that aids water retention and may mitigate climate change). “It’s a terroir-amplifier,” he asserts, adding that he’d also like to try growing vines from seeds, creating new biotypes which could create more complexity.

Elin then comments that his latest venture would have caused her to ask if it was a joke: He has entered what may seem like an unlikely alliance, she notes; his business partner is the giant E&J Gallo, one of the world’s largest wine operations. They approached him, he says – they wanted to push themselves; we’re from different cultures, but learning from each other. She asks what the prospects are. He replies that he hopes it will go on for a long time. It’s focused on southern French and Rhône varieties, but in a cool-climate area of California’s Central Coast; the aim is to make distinctive, elegant wines. So far, there are four wines planned, a Rosé and three reds. “I’d love to make whites too,” he comments, pointing out that the brand is called The Language of Yes.

Elin then asks about changes over the years, and he responds with a wry laugh, “It doesn’t have to be Cabernet, there are plenty of really interesting grapes, from Italy, Greece, many places. We don’t take advantage of the great freedom we have to grow grapes wherever we want, it’s a great missed opportunity.”

Elin agrees, and asks what he’s most proud of, and still hoping to accomplish. He says he’s proud of having pushed himself to take chances, and still looking ahead. (“Maybe it’s time to get a little more focused,” he adds with a laugh.) Elin asks him about the availability of the wines from The Language of Yes, and he says some are being bottled right now, and all should be available by Spring 2022. Elin concludes by saying that after tasting them recently and finding them delicious, she looks forward to actually drinking them.

Running Order:-

-

0.00 – 15.57

“I think my epiphanous wine was the ’64 Cheval Blanc”

– How Randall Grahm changed his career from philosophy to winemaker.

– Kermit Lynch’s influence on Randall Grahm.

– Founding Bonny Doon and his original quest to make Pinot.

– How he became the champion of Rhone varieties in California.

-

15.58 – 22.00

“I should have sold the whole company at the time not just Big House and Cardinal Zin”

– The launch of new brands after founding Bonny Doon.

– Working with Ralph Steadman, the British illustrator on the labels. -

22.01 – 28.32

“It’s a double-edged source being known for humour, the result maybe the wines not being taken as seriously due to the humorous labels”.

– Death of the cork dinner in New York with Jancis Robinson delivering the eulogy.

– Humour in wine.

– Popularising the screwcap, pioneering cryo-extraction.

– Working with Chuck House, the label designer.

-

28.33 – 39.00

“In California, we can control many aspects of the winemaking process, but at our peril—we can miss out on the interesting parts, those we can’t control.”

– Randall talks about why he is excited about his new venture the Popelouchum Vineyard in San Juan Bautista.

– Making wines of place instead of technique.

– The three projects at Popelouchum, including self-crossing varieties and breeding new varieties.

– Working with Serène, the antique variety of Syrah.

-

39.01 – 52.49

“I joke that Bambi meets Gonzilla”

– Randall discusses his new partnership with Gallo, “the Language of Yes”, the varieties they are producing from the Central Coast Santa Maria Valley and his hopes for the future of the project.

– Randall’s views on today’s California wine industry.

RELATED POSTS

Keep up with our adventures in wine

Alexander Van Beek, Estate Director of Château Giscours and Tuscan estate Caiarossa.